Lessons Learned From a Wildfire Close Call in Southern California, Part Two: Insurance and Risk Exposure

How has the California insurance market responded to increasing wildfire risk?

As discussed in the previous post in this series, a series of recent fires in Southern California caused significant harm, but wildfire adaptation and preparedness helped to protect the towns of Wrightwood and Angelus Oaks from the worst-case scenario in which fire destroys an entire community. However, many other communities are not as well-prepared for fire, and high exposure to fire risk can make it difficult for residents in these areas to acquire insurance. The combination of high fire risk, widespread underinsurance, and the structure of the state’s insurance market mean that—in the event of a catastrophic fire that destroys a community—many survivors will lack adequate resources to rebuild, but the resulting insurance claims could still be large enough to threaten the viability of the insurance industry statewide. In the previous blog post, we discussed the near miss that communities in the Big Bear Lake region of San Bernardino County recently experienced during last month’s Line Fire. In this post, we examine the potential effects of a catastrophic wildfire in the Big Bear Lake area for residents and insurers.

Un- and underinsurance

Because insurers are reluctant to write home insurance policies that include wildfire coverage in California, especially in areas they view as exposed to elevated wildfire risk, insurance in these areas is increasingly unavailable or unaffordable. As a result, many homeowners in areas like Big Bear Lake are uninsured or underinsured against wildfire. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey, there are approximately 428,535 owner-occupied homes in San Bernardino county. Approximately 7% of these homeowners are without a mortgage and are paying less than $100 for insurance annually, indicating that they are either uninsured or significantly underinsured, and 37% of homeowners with or without a mortgage are paying less than $1000 for insurance annually, suggesting that their homes are likewise significantly underinsured.1 In the event of a catastrophic wildfire that destroyed their homes, these homeowners would be left either with no resources or with inadequate resources to recover from the fire,2 and many would likely move out of the region rather than choosing to rebuild. The same is true for community members who are renters rather than homeowners. Many renters don’t have renter’s insurance, and even for those who are insured, renter’s insurance generally covers only personal property, with relatively limited coverage for costs incurred in the immediate aftermath of a fire like the living expenses involved in relocating and finding a new job and residence.

Even for community members who are insured homeowners, the claims process involved in filing for a loss due to a catastrophic wildfire can be convoluted and stretch on for years. Therefore, in the immediate aftermath of a fire, many of these households would also be likely to lack the resources needed to relocate and cover living expenses in the near term. In all of the above cases, the result would be additional suffering beyond the initial destruction caused by the fire, as well as barriers to rebuilding that could cause many residents to move out of the area permanently, an outcome that could effectively destroy the community.

California FAIR plan

Historically, California has responded to the problem of insurance unavailability through the FAIR plan, a state-created “insurer of last resort” that private insurers are required to participate in as a condition of doing business in the state insurance market. For homeowners in high-risk areas who aren’t able to acquire insurance through the conventional insurance market, the FAIR plan offers insurance for the risk in question. While the FAIR plan can be expensive and is a much more limited insurance product than traditional home insurance, it writes policies for all eligible applicants and satisfies the conditions of mortgages that require the mortgagor to obtain insurance for their property. As a result, many Californians living in high-risk areas like Big Bear Lake have turned to the FAIR plan, and the total number of Californians enrolled in the FAIR plan has greatly expanded in recent years.

Because it is an insurer that writes policies in high-risk areas, the FAIR plan’s exposure to potential damages is large, far exceeding the amount of assets it has on hand to pay for claims. In the event that claims under the FAIR plan exceed available resources, the FAIR plan is authorized by the state to cover the difference by assessing against the insurers which participate in it, in proportion to their market share of the California home insurance business. Contrary to the original purposes of the FAIR plan, this has contributed to the problem of insurance unavailability: because writing more policies, regardless of whether the policies themselves are in low- or high-risk areas, means an insurer will be exposed to the risk of a large assessment in the event that the FAIR plan requires it, insurers have acted to reduce their risk by writing fewer policies or ceasing to offer insurance in California entirely.

What would the effects be of a fire in the Big Bear Lake area?

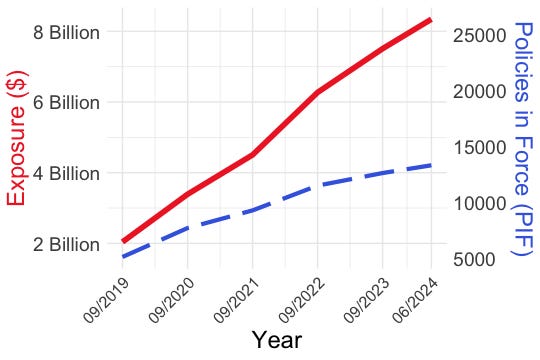

Fair Plan Exposure & Policies in Force for Big Bear Lake and Big Bear City

As of June 2024, 13,314 homeowner and commercial policies in the Big Bear Lake area are written by the FAIR plan, representing $8.3 billion in exposure. In the event of a catastrophic wildfire that destroyed a community in the area, the result would be a claim under the FAIR plan that would almost certainly be greater than the roughly $2.7 billion that the FAIR plan has on hand to pay,3 meaning that the FAIR plan would be required to assess against insurers. In the worst-case scenario in which every property with a FAIR plan policy in the area is destroyed, more than $5 billion would need to be assessed. Such an assessment has not occurred in the last several decades, but the California Department of Insurance has recently announced how it plans to conduct one if needed, and has additionally announced new regulations intended to prevent the need for an assessment of this kind. While this strategy may succeed in the long run, for the time being, the possibility of a FAIR plan assessment due to a catastrophic fire in an area like Big Bear Lake still represents a massive potential loss that could outweigh years of profits for insurers statewide. This risk exposure makes insurers more averse to writing policies in California, which contributes to the unavailability and unaffordability of insurance—a crisis which, in turn, causes homeowners to go uninsured or underinsured as described above, reducing communities’ ability to recover from catastrophic wildfires.

How can we prepare for future fires?

A scenario like the one described here is avoidable. To improve adaptation and protect communities like those in the Big Bear Lake area, the state and federal government should increasingly incentivize and prioritize mitigation measures like home hardening and prescribed fire that worked to protect the communities of Wrightwood and Angelus Oaks. In addition to reducing risk on the ground, these measures also reduce the potential economic damages from a wildfire and make insuring properties less financially risky, which can make insurance easier to access and more affordable for homeowners. The alternative—underinvestment in pre-fire mitigation and excessive reliance on suppression—has proven to be both impracticable and dangerous in the long term. Unless we act quickly to reduce the consequences of future fires, California’s luck may soon run out.

Eric Macomber joined the Climate and Energy Policy Program and Stanford Law School as a Wildfire Legal Fellow in September 2022. His work focuses on law and policy issues relating to wildfire and the wildland-urban interface.

Nam Nguyen joined the Climate and Energy Policy Program as a Stanford Postdoctoral Scholar in June 2024. His work focuses on wildfire policy challenges in California and the western US that inform interventions that support improved availability of homeowner insurance.

The average annual insurance cost of a $600,000 home in California is $2,598.

While it’s possible that some resources or other aid would be made available from the state or federal government, it isn’t guaranteed—for instance, a catastrophic wildfire might happen while the government is experiencing a budget crisis, or when the relevant agency is low on resources or responding to another disaster at the same time.

$200 million in surplus and $2.5 billion in reinsurance (insurance that insurers buy to cover their risk from catastrophic losses) as of March 2024.