Lessons Learned From a Wildfire Close Call in Southern California, Part One: Community Adaptation

What can we learn about wildfire risk and adaptation from recent fires?

This September, communities in Southern California faced three simultaneous wildfires in Orange, Los Angeles, and San Bernardino counties. These fires caused the evacuation of thousands of people from nearby areas, increased exposure to dangerous smoke and air pollution, and, in the most extreme cases, led to the destruction of homes and other structures. However—due to a combination of the hard work of fire agencies and other first responders, pre-fire planning by communities and homeowners in the region, and good luck—all three fires avoided the worst-case scenario in which a wildfire destroys an entire community.

This outcome was not guaranteed. In recent years, a series of catastrophic wildfires with deadly consequences have occurred in California, including the fires that occurred in 2017 across the northern part of the state, the 2018 Camp Fire, and the 2021 Caldor and Dixie fires. Factors including the effects of climate change are increasing the likelihood of severe wildfires in California and across much of the United States, even in areas that have little prior history of wildfire, as was shown by the highly destructive fires that took place last year in Hawaii. If the circumstances had been slightly different last month, any of the three Southern California fires could have been catastrophic. In addition to the direct and indirect harms that such a fire would cause to health and safety, natural resources, and property, this would also have serious consequences for the state’s already-precarious insurance industry, making it even more difficult for survivors and affected communities to recover from disasters.

In the aftermath of last month’s fires, it’s important to recognize the efforts that helped prevent these fires from destroying communities, understand what the statewide consequences of a catastrophic fire would be, and continue supporting work to mitigate the harmful effects of wildfires. To that end, this blog series will analyze two case studies and one potential scenario drawing on Southern California’s recent wildfire experience.

How can communities prepare for wildfire?

One explanation for the comparatively mild impact of these fires is that many of the people in harm’s way worked in advance to reduce the impact of wildfires on their communities. For instance, part of the Bridge Fire that spread in Los Angeles and San Bernardino Counties burned within the boundary of Wrightwood, a town in the San Gabriel Mountains. Similar communities have been destroyed in similar circumstances in earlier California fires, because wildfires that enter a developed residential area can spread quickly: when a single house burns down, the embers from that fire can ignite the homes nearby, which then ignite the homes near them, and so on until the entire neighborhood is burned. However, in Wrightwood, less than 1% of houses burned. One reason for this outcome is that the community conducted extensive fire mitigation work in advance, including retrofitting homes with more fire-resistant materials and maintaining a perimeter clear of potentially flammable material like vegetation around their homes. Both of these measures can greatly reduce the odds of an ember from a nearby fire igniting a house, which, in turn, stops fires from spreading throughout the community.

Wrightwood: defensible space around a home, April 2023

Wrightwood: defensible space in use by firefighters, September 2024

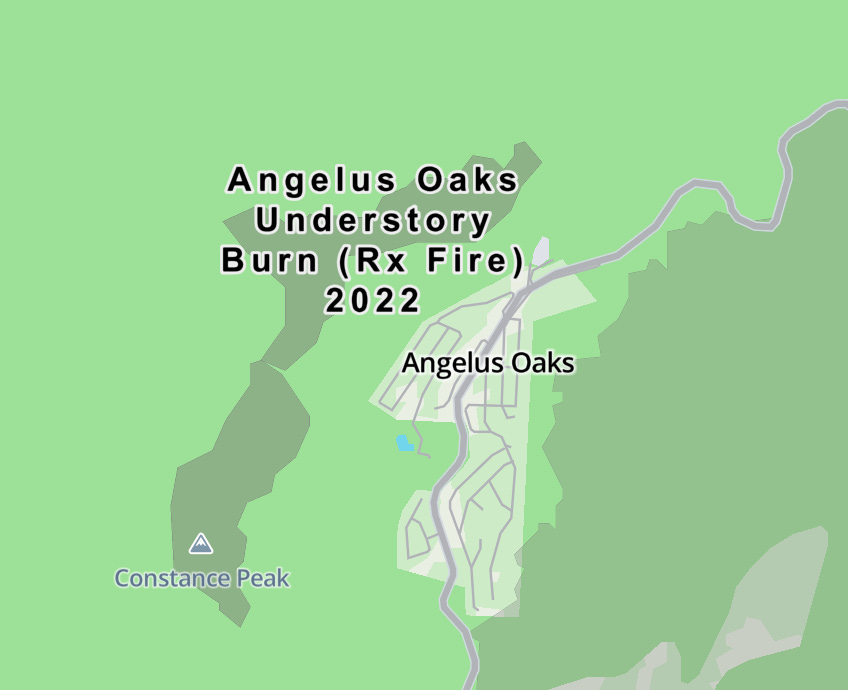

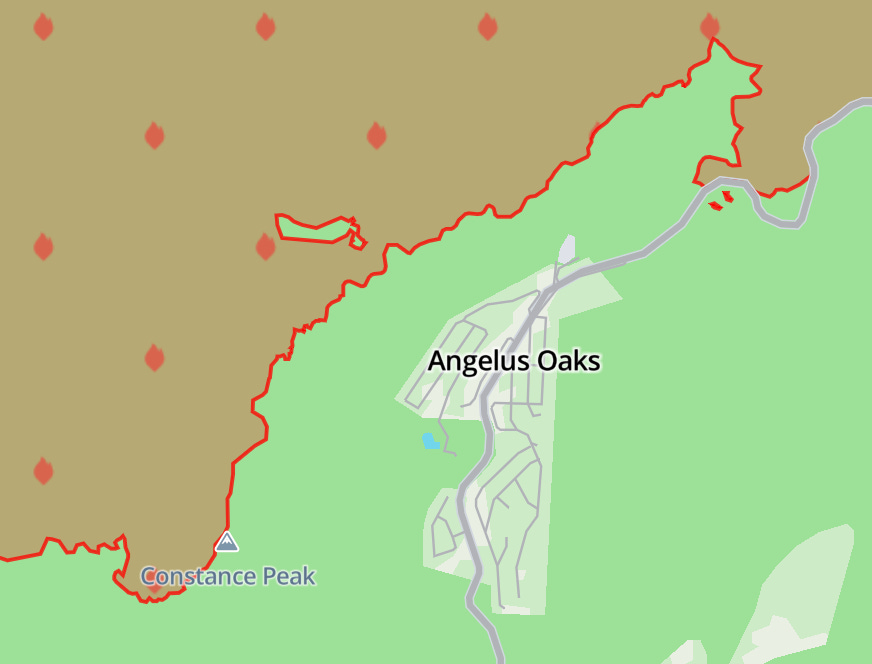

Another important tool that can mitigate the risk of wildfire is reducing the amount of flammable material like dry brush and dead vegetation in fire-prone areas. While it’s too early to say for sure exactly why the Line fire, which occurred in the San Bernardino Mountains, behaved as it did, one potential reason that firefighters were able to prevent the fire from entering the community of Angelus Oaks or expanding to threaten the nearby Big Bear Lake area was a lack of flammable vegetation in the area that could have served as fuel for the fire. Fuels in regions adjacent to the area burned by the Line Fire had been reduced in two ways: first by a recent wildfire,1 and second by a series of prescribed fires that deliberately burned vegetation in a controlled manner, one of which was conducted on federal land nearby earlier this year. Similar to the work that Wrightwood did to reduce fire risk to homes, prescribed fires like those used in the Angelus Oaks area can help prepare for wildfires in advance by reducing the amount of flammable materials in areas at risk of fire, which slows the growth of future fires and protects nearby communities.2

Angelus Oaks: 2022 prescribed fire perimeter

Angelus Oaks: 2024 Line Fire perimeter

Wrightwood and Angelus Oaks are examples of successful adaptation making it possible for communities to survive fires that might otherwise have been catastrophic. However, they also serve as a warning: across California, even though millions of homeowners are exposed to wildfire risk, very few communities are likely to be as well-prepared for fires as Wrightwood, and prescribed fires like the one conducted near Angelus Oaks are not being implemented at the scale needed to adequately reduce the risks posed by wildfire. As we’ll discuss in the next post in this series, this exposes communities across California to elevated wildfire risk, which—in addition to the direct dangers that wildfires pose—also makes insurance harder to acquire and reduces the resources available in the aftermath of a fire.

What if the Line Fire reached Big Bear Lake?

While the effects of these recent fires were serious, Southern California arguably benefited from a lucky break last month. If, instead of the cool, humid weather that arrived in the middle of September and allowed fire crews to make progress containing the wildfires, the weather had remained hot, dry, and windy, as is increasingly the case in the region, the fires could have burned hotter and spread much more quickly, and their consequences might have been much more severe. One illustrative example is the Line Fire. If weather conditions had been less favorable, the fire could have followed wind flowing over the dry Santa Ana River drainage to areas that have not been burned by wildfire or prescribed fire in decades, and which, as a result, are full of highly flammable material like dry brush and dead vegetation. This rich fuel could cause the fire to spread quickly and threaten communities in the Big Bear Lake area.

While the Big Bear Fire Department, which serves Big Bear Lake, Big Bear City, and other nearby communities, has encouraged residents to create defensible space and to retrofit their homes to protect against fire in a similar manner to the residents of Wrightwood, and some prescribed fire projects have been carried out in the San Bernardino National Forest closer to the Big Bear Lake area than the recent Angelus Oaks burns, it’s not clear how extensively these programs have been implemented or how effective they would be in the event of a high-intensity fire like previous California catastrophic wildfires. As the increasing unavailability of conventional property insurance in the area indicates, perceived wildfire risk in the region remains high despite the existence of these programs. If the Line Fire, rather than being contained near Angelus Oaks, had continued expanding until it reached the Big Bear Lake area, it’s very possible that the result would be a catastrophic fire.

In addition to the direct harm that would be caused by such an event, two seemingly contradictory—but related—negative outcomes would also be likely. First, because a large number of residents of the area are uninsured or underinsured, many people would be left without the resources needed to relocate or rebuild their homes. Second, the amount of damage in the area that is covered by insurance could be large enough to throw the insurance market for the entire state of California into turmoil. In the following post in this series, we’ll unpack each of these outcomes and discuss how they can be prevented.

Eric Macomber joined the Climate and Energy Policy Program and Stanford Law School as a Wildfire Legal Fellow in September 2022. His work focuses on law and policy issues relating to wildfire and the wildland-urban interface.

Nam Nguyen joined the Climate and Energy Policy Program as a Stanford Postdoctoral Scholar in June 2024. His work focuses on wildfire policy challenges in California and the western US that inform interventions that support improved availability of homeowner insurance.

The 2020 El Dorado Fire.

Other forms of beneficial fire include burning piles of vegetation collected as a result of forest stewardship activities, the use of managed low-intensity wildfires, and Native American cultural burning practices.